Copyright: Finn Graff/Dagbladet

What do we see?

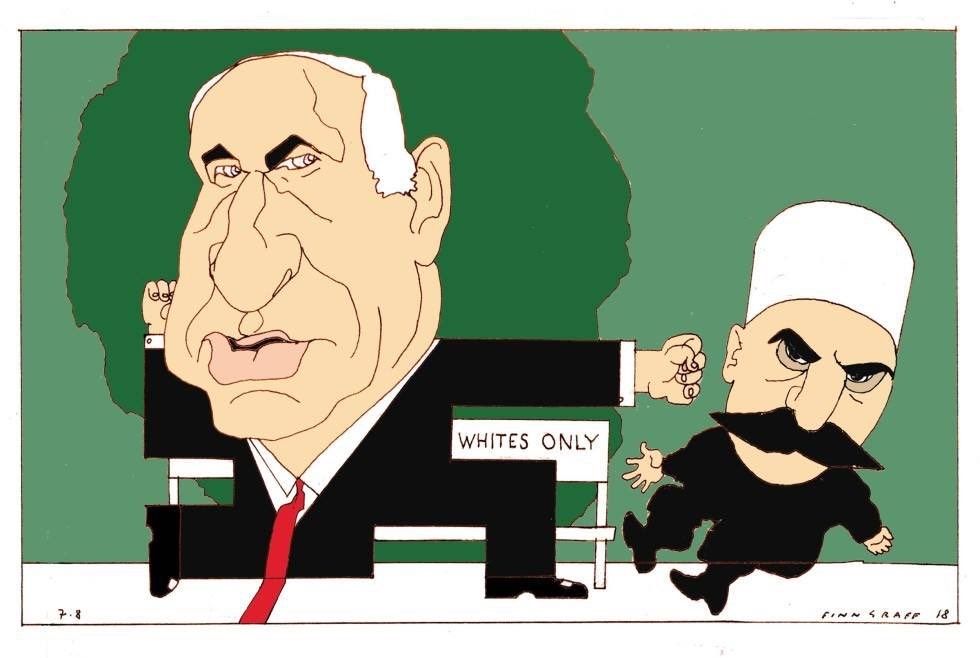

This cartoon was published in the Norwegian newspaper Dagbladet in 2018. It is drawn by renowned cartoonist Finn Graff. The cartoon depicts former Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, knocking a Druze off a park bench, with the inscription “Whites only”. Netanyahu is furthermore drawn so that his posture has the form of a Swastika.

The cartoon was published together with a commentary about the Druze minority’s opposition against Israel’s then new Nation-state bill, specifying Israel as a Jewish nation-state. The cartoon sparked a minor international controversy, as the Israeli ambassador to Norway publicly condemned the drawing, calling it “an example of the most repulsive imaginable anti-Semitic imagery”, and filing a complaint to the Norwegian Press Complaints Commission. The incident got covered not only in Norway, but also in Israeli media as well as European legacy press and Jewish organisations. Eventually, Dagbladet was acquitted by the Complaints Commission, an independent body organised by media outlets and based on membership and commitment to an ethical code.

Which public issue was addressed here?

This cartoon incident has two major characteristics that are quite typical for humour controversies in the Norwegian, and probably European, public sphere. The first concerns the core of the controversy – what the issue deemed problematic is. Here, it was anti-Semitism, in other words, an issue of race and ethnicity. The clear majority of humour controversies in Norway in the last years has concerned race and ethnicity, as humour has been accused of being racist, anti-Semitic, or promoting racial and ethnic stereotypes. Other kinds of controversies, like when the public broadcaster NRK was accused of trivialising rape of men, are more rare, and rarely get off the ground as they get much less media coverage and fewer actors get involved.

Secondly, the participants in the debate on the Netanyahu cartoon are what can be called “the usual suspects”. Humour controversies about the same issues tend to mobilise the same actors, which indicates that these actors use such controversies in order to gain public access and spread their own views in the public sphere. It is important to note that this should not be read as indicating some kind of conspiracy or delegitimising of the different actor’s views about the controversial piece of humour. Rather, it points out how the public sphere is infused with power and self-interest, and that actors who already have access to the public sphere use incidents like humour controversies to dramatize differences of opinion and thus become more visible in the public. In this case, we see this pattern clearly: The participants are, on the one side, a Christian pro-Israel organisation named MIFF, the Israeli embassy, and a columnist formerly affiliated with the Holocaust research centre. On the other side, we find the publisher of the controversial piece of humour, Dagbladet, which presents a quite unapologetic defence.

What does the humour do?

This incident also displays a third characteristic typical for humour controversies in the Norwegian public sphere: the arguments that are used to support the publication of the allegedly offensive/damaging piece of humour. These tend to be formulated around lines like how satire by nature is transgressive, free and enjoys more liberties than for example journalism or commentary. In other words, the defence of satire, including cartoons, is based on freedom of speech arguments that gives satire a special status, increased space for transgressions and increased protection. In this case, Dagbladet’s political editor defended the cartoon by stating that “It is in the nature of the satirical cartoon that the tolerance for transgressions should be higher”, while the Complaints Commission argued in their acquittance that “satire has a more free role in the Norwegian press”. It is interesting to note that this principled defence of satire gives it “a license to transgress”, but without stating any benefits satirical transgression might have. Why is it important that satirical cartoons are able to offend, also in ways other media genres should not be able to do? These questions get little attention in humour controversies in the Norwegian public sphere, which means that the particularities of humour in the public sphere are sparsely discussed.