What do we see?

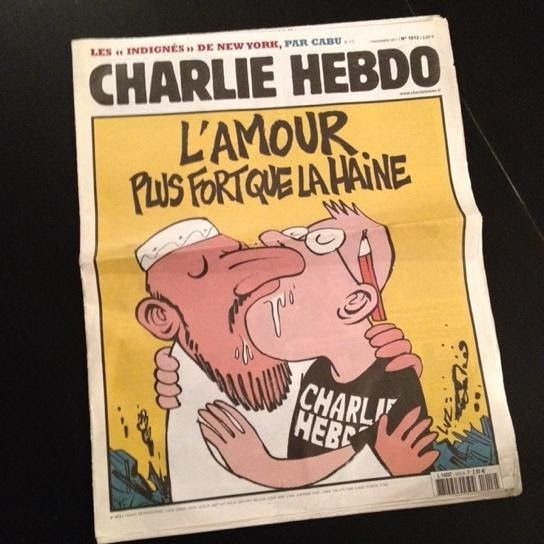

On November 8, 2011, the front page of the weekly Charlie Hebdo showed a cartoon, captioned “Love is stronger than hate” by cartoonist Luz (pseudonym of Renald Luzier). The image was published a week after a fire-bomb attack by radical Muslim activists, in which the editorial offices were destroyed.

This cartoon has become immensely well-known: it dons sweaters and T-shirts, and often appears next to publications about Charlie Hebdo (ironically, probably also because unlike other controversial Charlie Hebdo cartoons, this one doesn’t show the prophet Muhammad in person). Luz also drew the cover in response to the second, much more serious attack on Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015. In this attack, 12 people died. Luz was one of the few survivors of this attack. The 2015 cover shows a teary-eyed Muhammad holding a sign saying “Je suis Charlie” and the caption “tout est pardonné.” (All is forgiven).

Both cover images are simultaneously puzzling and provocative. As often with Charlie Hebdo, you find yourself wondering: obviously someone will be insulted by this—but what does it mean? Whom are they addressing? What are they trying to say? Should I, personally, be offended?

What public issue is addressed here?

After these attacks, Charlie Hebdo became a pan-European symbol for the power of satire: humor and laughter as the antidote to fanaticism and repression. Especially after the attack of 2015, which gave rise to a global wave of people claiming they, too, were Charlie, people left and right claimed their support of satire as the hallmark of Western/European/modern) freedom. Often, (radical) Islam was identified as the main threat, but it was also linked to other issues, from media commercialism to the decline of the spirit of the 1960s. Remarkably few of these endorsements have paused to ask what Charlie Hebdo teaches us about satire: that satire is a strong but elusive force, not easily harnessed for political purposes.

What does the humor do?

Both covers use a similar humorous technique: a clash between pious, almost biblical captions and exaggerated cartoonish images with bold lines, big noses and faces dripping bodily fluids (though with opposite connotations – spit and tears). The exaggerated representations of Muslim men represent another humorous technique: transgression, the willful disregard of social norms. This transgression is not play or juvenile provocation, but an act of reckless defiance. The 2015 cover emphasizes this by proclaiming itself an “Irresponsible journal”. But what does this transgression defy? Unlike many satirical publications, Charlie Hebdo rarely makes a clear political statement. Instead, there is something deeper or darker. If anything, the antagonist is power itself. Throughout its history, Charlie Hebdo has opposed rigid social codes and their hierarchical enforcers of any creed or conviction. This was what brought about its clash with Islam.

The images tell us this is humor. But the captions add a puzzling, absurdist counterpoint, setting off an unending interpretive loop. Is this serious, or another joke? So: let’s say it’s serious. Then the calls for forgiveness and love are a magnificent gesture. It seems to appeal to ideals of love and forgiveness also embedded in the religions Charlie Hedo so likes to taunt. But then I pursue the other train of thought: let’s say it’s a joke. They are challenging the religious by adding insult to injury, claiming love and forgiveness against their pious claims of love and brotherhood. Or maybe they are provoking us, the readers? At a time when anger, bitterness and grief are to be expected, Charlie Hebdo again defies our expectation, disrupting the order of things by speaking of forgiveness and love – although love is of a particular kind that some also find transgressive.

Thus, a cartoon like this keeps the reader trapped in a loop: Is it serious? If so, what does it mean? Or is it not serious? But then, where is the punchline? Does it mean something? Should I laugh? The image itself offers no final solution. Instead, it challenges our thinking in ways that only good satire can do. Its ambiguity suspends meaning. And this keeps the public temporarily suspended, too.